You are currently exploring the Fundamentals Library, which is designed to provide a basic overview of the topics that are covered in other longer articles. This article is a part of the Training Organization section.

Lighter Training

Lighter training is a very common tool used in training programming. We could define such a period as a set of training sessions with reduced relative demands compared to the usual training, achieved by a specific manipulation of training variables such as volume, load, or proximity to failure or exercise selection.

The style and length of the lighter training period can vary. It depends on goals, preferences, and practicality. The three main forms of lighter training are:

- Deload

- Pivot

- Taper

What Is Lighter Training Used For?

There are many different scenarios where a lighter training period can be potentially utilized. These can be split into reactive and proactive applications.

Reactive application is when a lighter training period is not a planned element of the training cycle, but rather something we use in reaction to some unplanned occurrence in training. Such occurrences can be:

- consistent stagnation

- connective tissue pain

- increased time or energy demands outside of training

- practical inability to train with normal conditions

- loss of motivation

Proactive application on the other hand is a planned element of the training program. Typically it is preceded by a period of high demand training, which goes beyond our recovery ability. Such a scenario is called overreaching (not to be confused with overtraining which is a chronic medical condition).

Sometimes, deload is used as a restoration after hard training which came due to other reasons (like competition). Other times, overreaching is planned ahead with the increase in performance post deload as a goal.

On that point, in the literature you can find terms like functional overreaching and non-functional overreaching. Functional overreaching refers to the short decrease in performance due to fatigue which in the long run is beneficial to the overall performance. Contrary to it, non-functional overreaching is when increased training loads don’t result in long term improvement of any kind.

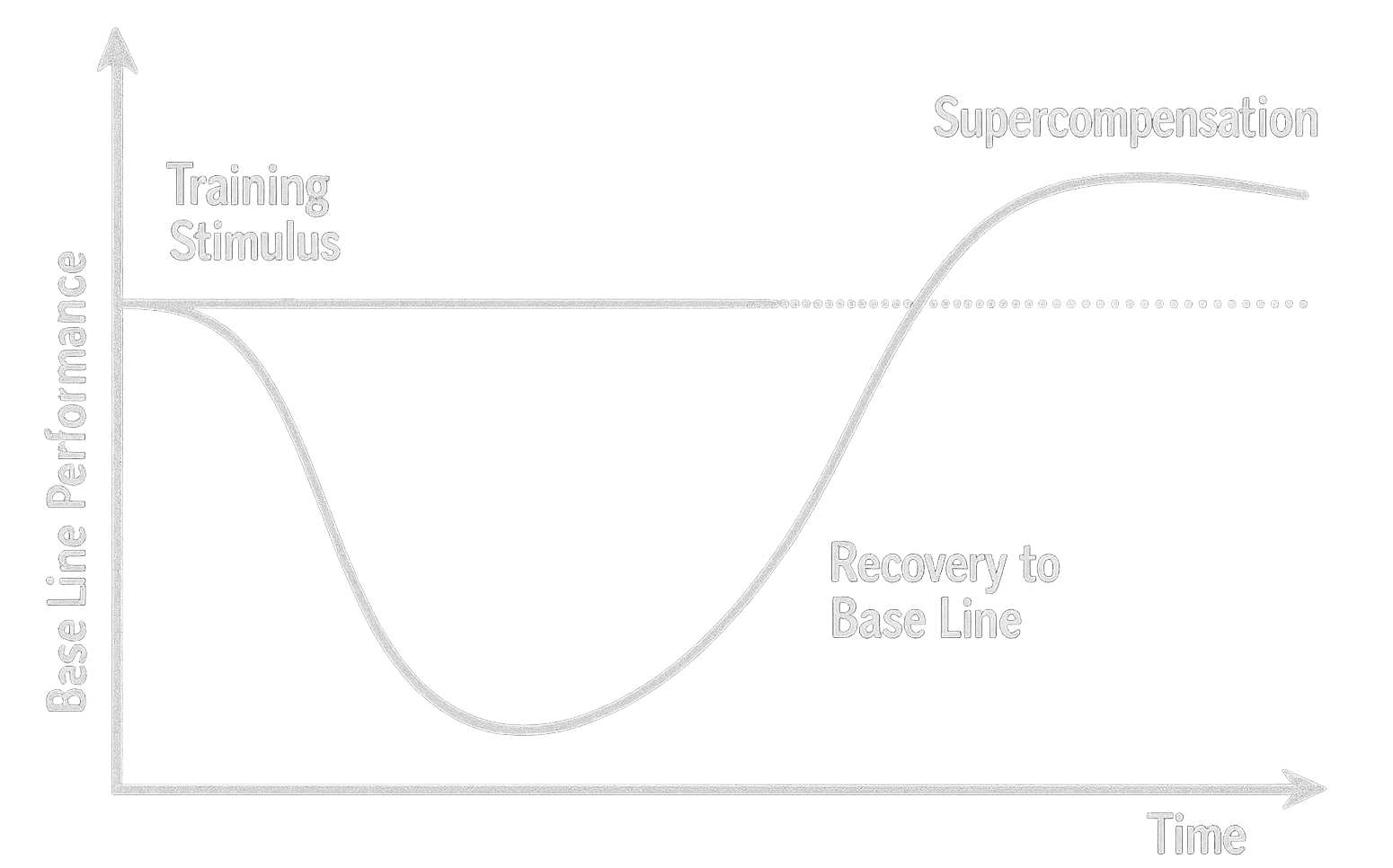

Supercompensation & Functional Overreaching

The idea of functional overreaching is based on the theory of supercompensation. The theory states that after a period of heavy training, a period of lighter training allows for some delayed adaptations to occur that increase the athlete’s capacity beyond what it was before the period of lighter training.

It is debatable whether supercompensation occurs as a result of delayed adaptations or as a result of a reduction in fatigue that “masks” the result of adaptations made throughout the program.

If the second is true, it would call into question the use of overreaching as a planned strategy, especially in non-advanced populations - since training in a fatigued state is likely to be less effective in creating adaptations than training in a non-fatigued state. This would also call into question the use of proactive lighter training periods.

In general, the current state of the literature does not clearly support (but does not completely refute) the idea of supercompensation after overreaching, being something else than just fatigue mitigation. It is certainly not a principle that should be followed, and it could potentially pose more risks than benefits.

Deload

Deload is the most popular way to perform a lighter period of training. It typically lasts one week and the general idea behind it is to maintain most of the characteristics of training while reducing its demands.

This is typically done by manipulating either volume, load, proximity to failure, or a combination of these.

Despite its popularity, deloading is an underexplored area of research. There are very few empirical studies comparing training with and without deloading, and those that do find no statistically significant differences.

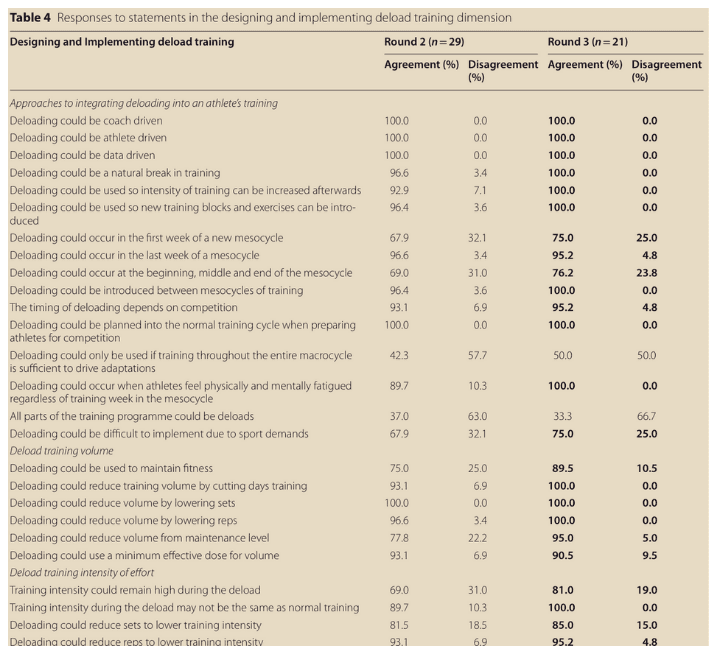

We also don’t have clear research-based guidelines on how to deload. An interesting study was conducted using the Delphi method (expert panel questionnaire). The panelists agreed that deloading can involve a reduction in volume through various means, and that training intensity can both increase and decrease during deloading, but that training volume must be reduced at the same time if we don’t reduce intensity.

Below is an excerpt of the table from the study. The biggest takeaway is that there are actually many ways to deload that coaches use.

From a purely physiological standpoint, the most sensible thing to do is to reduce the volume of work as a universal quantitative parameter. We could do this by reducing the number of sets per exercise or group of muscles trained by 50%.

Then, depending on the reason for deloading, different parameters could be modified in different ways. If we’re strength athletes, we probably don’t want to sacrifice heavy loads, but we can train 1-2 reps further from failure than we normally do. If we are dealing with connective tissue discomfort, a lighter load may be a better intervention. If we are tired from constantly pushing to the limit, we can reduce the proximity to failure.

Pivot

As mentioned above, a typical feature of deloading is that it reduces the demands on the training variables while maintaining the characteristics of the workout in terms of exercise selection.

A different and much less popular tactic is the so-called pivot. Pivot is a term that does not exist in the literature, and frankly, I’m not sure where it came from.

The idea is essentially that instead of keeping the characteristics of the program the same as during our normal training, we introduce completely different movement patterns.

It is somewhat similar to the idea of cross training in sports. According to this (also mostly anecdotal) practice, athletes of a given discipline participate in different disciplines, often as a form of mental recovery in the off-season.

This is a time to do exercises that we have always wanted to try, but never made room for in the program. There is a possibility that during this exploration we will gain some helpful insights that we can use in our actual programming.

Pivot might be a good strategy especially in case of a feeling of staleness and mental fatigue from training, as well as connective tissue issues that require complete rest from stressing a particular area.

Taper

Taper is a very popular concept in endurance and strength sports. Like the previous strategies, it involves a period of lighter training. Taper, however, is tied to a specific event, typically a competition. The whole idea behind tapering is to allow for recovery and to get rid of present fatigue.

Often it is part of peaking, which is the final stage before competition where we maintain a very specific practice to achieve the best possible result. Taper typically lasts from 1 to 3 weeks.

Taper is a popular topic in the literature, probably because of its association with competitive sports and because it is a low-hanging fruit when it comes to performance enhancement. It is documented that a well-executed taper can improve performance (usually in the range of 0.5% to 6%).

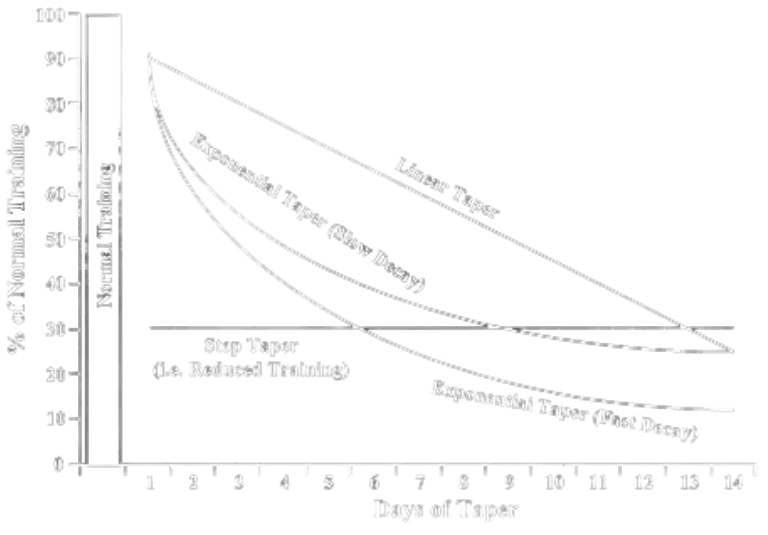

There are several ways to perform a tapering period. The decline in training load can be abrupt and sustained, it can be linear or exponential. There are reports showing benefits of the progressive rather than the abrupt decay.

The most important aspect of taper is that the characteristics of training should remain as specific as those displayed in competition. In the case of strength sports, this means that taper must include the use of high loads prior to the event and the manipulation of other variables to reduce fatigue.

Why Not Rest Week?

A question that is often asked in the context of lighter training (especially deloading, whose sole purpose is to make training less fatiguing) is - why not just stop training altogether for a week or a few days when needed?

This is a very valid argument that is actually not easy to argue with. Since the main goal of deloading is to reduce fatigue, taking a rest would do just that, and arguably make it better (while being more efficient in terms of time and energy).

In addition, anecdotally, when working with clients, I find that there is occasionally a reverse effect when it comes to motivation - clients often despise deloading and their motivation to train decreases because they feel that their training is pointless. This is especially true when the variable we are reducing is load.

The argument for deloading rather than taking a full period of rest is to make it easier to return to normal training as well as to experience less DOMS.

There is also an argument about motor patterns and coordination. For some more complex gymnastic skills, some element of practice might make the pattern less rusty when returned to on a regular schedule.

At the end of the day, lighter training is one of those subjects that should be heavily individualized based on our experiences. Too often it is being portrayed as a must have. At the same time however, we can’t dispute the possibility that it is an overall net positive to most people’s training, even if the results are mostly psychological.

Below you can answer a few question to get a recommendation on deloading:

Did you experience a drop in performance over the last 2–3 consecutive sessions?