You are currently exploring the Fundamentals Library, which is designed to provide a basic overview of the topics that are covered in other longer articles. This article is a part of the Anatomy section.

Movement Analysis

Movement analysis can be split into two directly related categories:

- Kinematics

- Kinetics

Kinematics is the study of motion, while kinetics is the explanation of motion. In kinematics of the human body we simply analyze and name motion, while in kinetics we look at the forces that interact with our body and analyze their influence.

To understand how forces affect motion in our body at a fundamental level, we must understand the general principles of how motion can be measured and described.

In calisthenics, knowing the basic mechanical principles of movement helps to understand the demands of the exercise, compare exercises to each other, and communicate accurately, for example with clients.

It is a basis for identifying muscle involvement in exercises and skills, analyzing the difficulty of exercises, their resistance profiles, and strength and difficulty curves.

position and direction. Both can be described mechanically, but in anatomy we use separate concepts specific to the joints we are working with. This article will unpack these concepts.

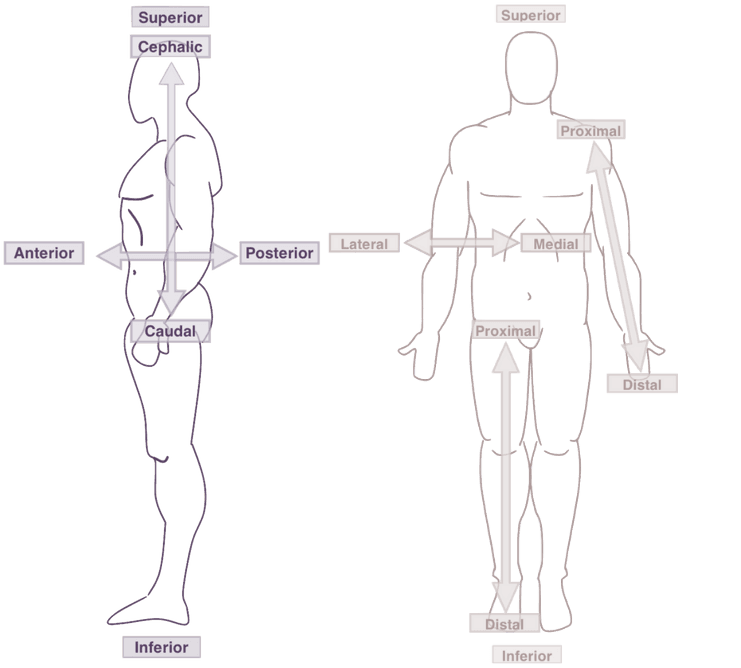

Anatomical Directions

The first thing worth bringing up are anatomical directions. Knowing this proper terminology can be very useful when describing exercises or pretty much anything related to human body structure:

- Superior - toward the top

- Inferior - toward the bottom

In anatomical terms you can sometimes notice the terms cranial (toward the head) and caudal (toward the feet). They are pretty much interchangeable with superior and inferior in our use cases.

Example - in tuck planche our center of mass is superior and in full planche it goes in the inferior direction in relation to tuck.

- Medial - closer to the midline

- Lateral - further from the midline

Example - you may have heard of injuries (often occurring in calisthenics) known as golfer’s elbow or tennis elbow. Golfer’s elbow is in medical terms known as medial epicondylitis - referring to the tendinopathy in the area of medial epicondyle. Tennis elbow refers to the lateral epicondylitis - referring to the tendinopathy in the area of lateral epicondyle.

- Anterior - toward the front

- Posterior - toward the back

Example - in rows and front lever we exert force in the posterior direction while in push ups and planche we exert force in the anterior direction.

- Proximal - closer to the body center

- Distal - further away from the body center

Example - you probably heard of muscle attachments (insertion points). Biceps brachii long head has its proximal attachment on the supraglenoid tubercle on the scapula. Its distal attachment is on the radial bone and forearm fascia.

Anatomical Planes & Axes

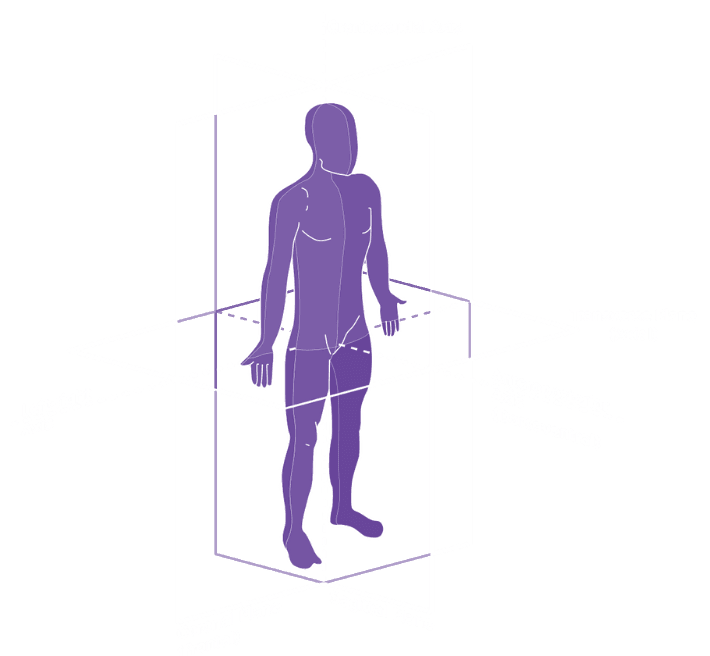

As explained in this article, we can simplify the location of motion using the concept of anatomical planes. Instead of using the coordinate system of each joint we analyze, we can use the coordinate system of our body as a whole.

The standard reference point is the anatomical position. A body standing upright with feet shoulder-width parallel and upper extremities outstretched with palms facing forward. You can see this position in the pictures in this article (for example the picture above).

We differentiate 3 anatomical planes:

- Sagittal

- Frontal (Coronal)

- Transverse (Axial)

If we perform any motion forward, we perform it in the sagittal plane. If we move to the sides - we move in the frontal plane. If we rotate some parts of the body to the left or to the right or we bring a segment of the body to or away from the midline - we move in the transverse plane.

What follows the anatomical planes are the anatomical axes:

- Anteroposterior

- Left-right

- Craniocaudal

Anatomical Motions

The most practical terminology group that you find in all exercise related education materials are anatomical motions. These are the actual motions that we perform during daily movement and exercise.

We will go over all primary body areas and movements in them. We won’t however focus on the specific joints where these motions occur, as that’s not so much related to the kinematics and functional anatomy, as to the anatomy (structure) itself.

Head & Upper Extremity Motions

Neck & Head

- Flexion

- Extension

- Lateral Flexion (Left & Right)

- Rotation (Left & Right)

Neck (being the cervical part of the spine) and head are actually independent anatomical segments when it comes to motion. However, since they are highly related when it comes to their function, we put them into a single category.

- Protraction

- Retraction

- Elevation

- Depression

Note that scapula motion is actually a result of movement in a couple of distinct joints. The other functions of the scapula (that cannot be isolated) are upward rotation and downward rotation which support the motion of humeral bone (shoulder motions).

Shoulder

- Flexion

- Extension

- Abduction

- Adduction

- Internal Rotation

- External Rotation

Sometimes as an extra anatomical motion the horizontal flexion and horizontal extension are listed. Mechanically, movements in the shoulder joints are a spectrum. From the anatomical standpoint and muscle function, the horizontal flexion and extension are pretty important motions, often occurring in the context of exercise.

Elbow

- Flexion

- Extension

- Pronation

- Supination

Pronation and supination typically refer to the forearm and not elbow, and that’s due to the fact this motion is not solely dependent on the joints in the elbow complex.

Wrist

- Flexion

- Extension

- Abduction

- Adduction

Fingers

Simplifying the segmentation:

- Flexion

- Extension

- Abduction

- Adduction

- Thumb Circumduction

- Thumb Opposition

Fingers are a complex set of segments. The primary movement that is a combination of many motions is gripping as well as opening the palm. We can also spread our fingers.

Trunk & Lower Extremity Motions

Spine

- Flexion

- Extension

- Lateral Flexion (Left & Right)

- Rotation (Left & Right)

All the mentioned spinal motions occur simultaneously in each joint of the spine. It is possible to roughly isolate movement in the cervical, thoracic and lumbar segments.

We must however remember that spine motion happens independently of the hip motion. For example in the spine flexion & extension animation, the model bends over in both spine and hips.

Hip

- Flexion

- Extension

- Abduction

- Adduction

- Internal Rotation

- External Rotation

Pelvis

On your exercise education journey, you have likely encountered the following terms:

- Posterior Pelvic Tilt (hip extension & spine flexion)

- Anterior Pelvic Tilt (hip flexion & spine extension)

Pelvis motion is basically the result of hip and lumbar spine action. Together they create the subtle motion of the pelvis which is actually essential to grasp from the standpoint of exercise.

Knee

- Flexion

- Extension

- Internal Rotation

- External Rotation

It is worth noting that knee rotation can’t anatomically occur when the knee is simultaneously locked in an extended position (0 degrees of knee flexion). It is because when the knee is locked in extension, the joint surfaces are tightly congruent, and knee ligaments are maximally taut.

Ankle

- Flexion (Plantar Flexion)

- Extension (Dorsi Flexion)

- Inversion

- Eversion

Toes

Simplifying the segmentation:

- Flexion

- Extension

- Abduction

- Adduction

Anatomical Motion VS Position

Much confusion is caused in the communication of anatomical motion by the conflation of anatomical motion and anatomical position.

It is important to note that position refers to the static condition - an angle in the joint. For example, the knee might be flexed to 90 degrees.

Movement, on the other hand, suggests the direction, trajectory, or the direction of the attempt of motion (even if the motion doesn’t occur). So, to give you an example, while my knee is flexed to 90 degrees, I can simultaneously initiate a knee extension motion (for example in a squat).

To give you another calisthenics example, in the Front Lever, our shoulders are at about 60 degrees of shoulder flexion. However, the movement attempt is shoulder extension. We attempt to extend our shoulders at 60 degrees of shoulder flexion.

On the other hand, in Back Lever our shoulders are at about 30 degrees of extension (sometimes called hyperextension). However, the attempted movement is shoulder flexion. We try to flex our shoulders at 30 degrees of shoulder extension.