To achieve peak athletic performance in calisthenics and any other sport/type of training, getting a good night’s sleep is just as important as a regular training program and a nutritious diet. Research shows that poor sleeping habits could impair the effects of training. It may lead to reduced muscle mass [1, 2] and strength [3, 4], longer recovery times [5], reduced motor coordination [6], even make one unconsciously tend towards eating more carbohydrates and fat [7-9].

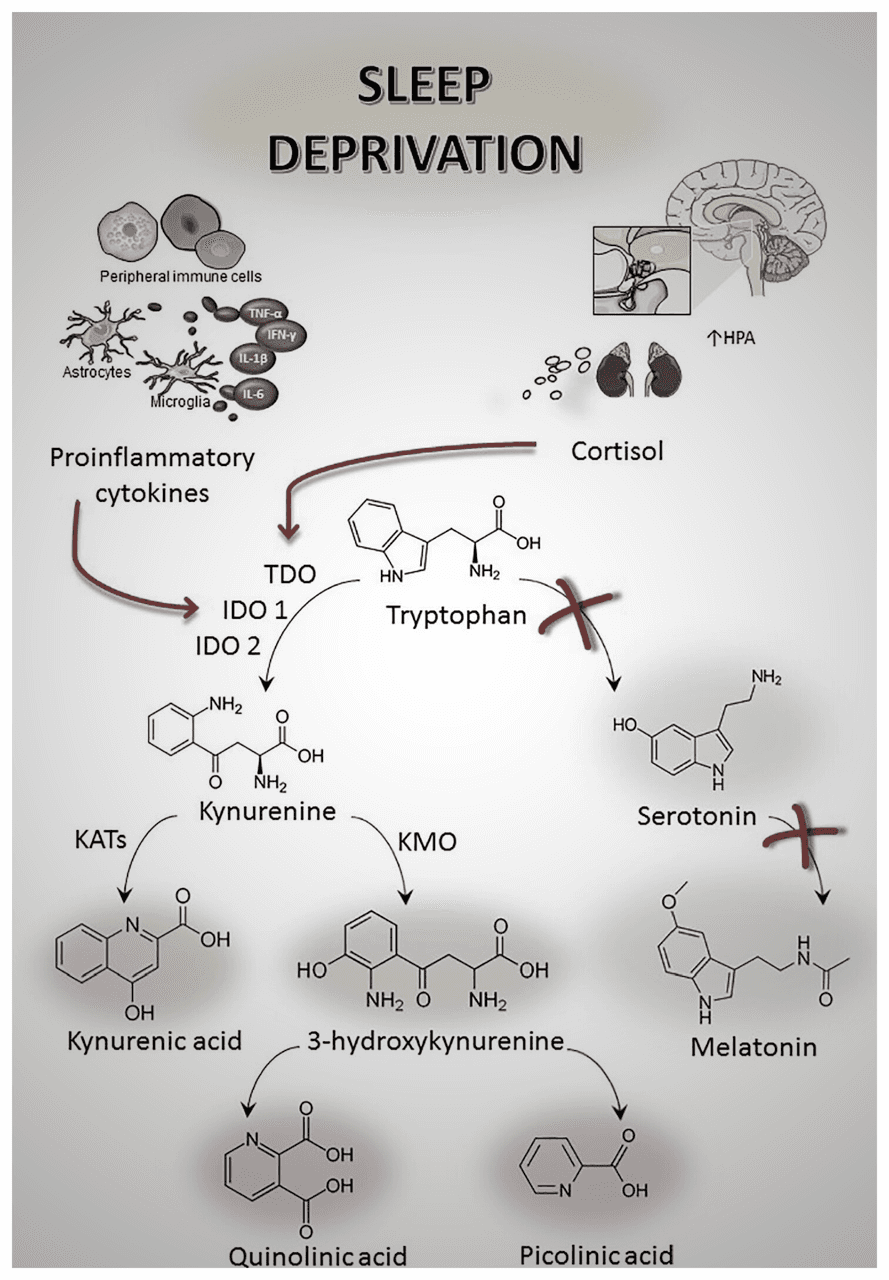

Although the underlying reasons are under active investigation, scientists agree that multiple processes are involved, including the accumulation of waste in the brain that is normally cleaned up after a good sleep [10]. This waste is thought to slow down the processes involved in learning, information processing, and motor dexterity [6, 11]. It also seems to elevate the cortisol levels [12] and increase insulin resistance [13] via the neuroendocrine axes.

Sleep and physical activity form a positive feedback loop, meaning that good exercise improves sleep, and vice versa [14, 15]. But on the other hand, even a single night of poor sleep worsens exercise quality, leading to another night of bad sleep, and spiraling on. To prevent this, certain evidence-based practices can be implemented, which are presented in the following paragraphs. These are curated for both professional and recreational athletes , with a deeper look into the scientific background of each.

How is a “good sleep” defined?

In medical terms, good sleep is one that is not disordered. Apart from sleep-related breathing and movement disorders (e.g. obstructive sleep apnea, restless leg syndrome, etc.), sleep disorders can be categorized into two main categories [16]:

- Parasomnias: disorders such as nightmares, sleep-walking

- Dyssomnias: disorders like insomnia (difficulty initiating and/or maintaining sleep), hypersomnia (excessive sleeping), narcolepsy (dozing off while awake), etc.

For most adults, this translates to a sleep that has the following properties [16, 17]:

- lasts 7–9 hours long, neither less nor more

- is in accordance with one's chronotype

- no waking up in the middle

- takes no more than 30 minutes to initiate (i.e. falling asleep in under 30 minutes)

- involves smooth fluctuations between different sleep "stages"

- involves no unusual behavior (like sleep-walking)

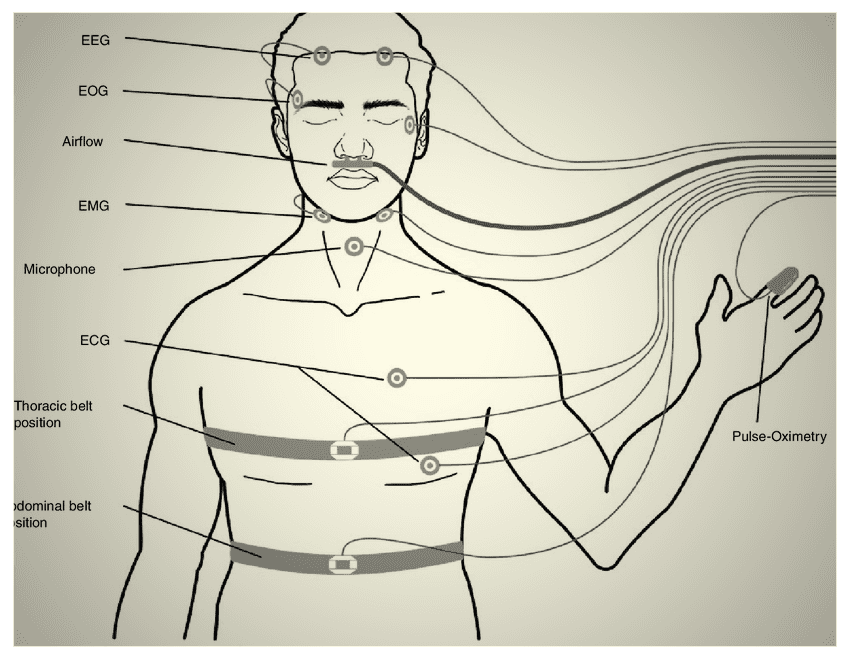

These qualities are correlated, meaning that if one is compromised, others may be compromised as well (at least, to some degree). Sleep doctors use a sophisticated method, called polysomnography (PSG, or simply a “sleep study”), to measure the properties of one’s sleep objectively, and assess whether it is “good” [18].

Since undergoing a PSG is not convenient (it involves at least one night of hospitalization, and attachment of more than 20 electrodes to one’s body while they sleep overnight [18] let alone costs) sleep scientists created validated self-reporting questionnaires to assess one’s sleep subjectively. Evidence is mixed on whether the results from these questionnaires correlate well with PSG assessments [19, 20], nevertheless, these may roughly estimate one’s sleep wellness.

A famous one (the one I have encountered the most throughout my own research, to be more accurate) is the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) questionnaire. Here you can take the questionnaire and here you can assess the score. The score, which can range from 0 to 21, is calculated by summing the seven component scores. A higher score signifies lower sleep quality; notably, a score exceeding 5 is indicative of significant sleep issues. It can provide an overall idea of your sleep wellness.

A more accurate and objective option, emerging recently thanks to the global use of smart wearable devices, is actigraphy [21]. This method involves feeding data from accelerometers (movement sensors, usually placed on the wrist or hand) to complex algorithms, which in turn, return a somewhat-accurate measurement of one’s sleep parameters, and subsequently, its wellness. Research shows that commercial wearables (such as the “watch” models by Apple [22], Samsung [23] and Fitbit [24], as well as “ring” models by ŌURA [25]), could accurately measure one’s sleep parameters in up to 60-70% of cases, thus, providing a relatively-reasonable estimation of its wellness (when used consistently for a certain period).

Actigraphy’s important drawback, however, is that it could not reliably distinguish motionless wakefulness from sleep. This is due to the fact that it relies on the body's movements to distinguish sleep from awake states. So, for example, if one is awake in bed but remains still, there is a high probability that the actigraphy device misclassifies it as sleep [26]. To resolve this issue, some devices feed additional data from their pulse rate, blood oxygen, and temperature sensors into their sleep-detecting algorithms. This does improve the devices’ performance, but only to a small extent, as indicated by recent research [27-29]. Unlike PSG, therefore, these devices are not optimal for measuring sleep quality in individual nights, but better if used to screen for sleep problems over a certain period of time (weeks to months, so that we could be sure that an adequate number of error-free measurements are made).

Athletes should pay special attention to this point. In this context, a recent study has shown that in short-term, people’s own satisfaction with their sleep was associated with their perceived level of well-being, while their actual objective sleep measurements were not [30]. In line with this is our experience with some athletes using actigraphy-capable devices who check their last night’s sleep quality estimate every day.

These athletes subconsciously feel worse during the day, when their device indicates that they have had a bad sleep last night, even though the device’s indication might have been errored. We would, hence, suggest that if using actigraphy capable devices, it is best to look at the sleep quality estimates only once in a while (once every two to four weeks or so).

This leads us to the evidence-based tips to achieve an optimal sleep.

1. Have personal sleeping schedule

To achieve the first three qualities of a healthy sleep, (i.e., getting the right amount of it, fitting it to chronotype, and not waking up in the middle) it is recommended that each person dedicate a specific, uninterrupted period of the day exclusively to sleep.

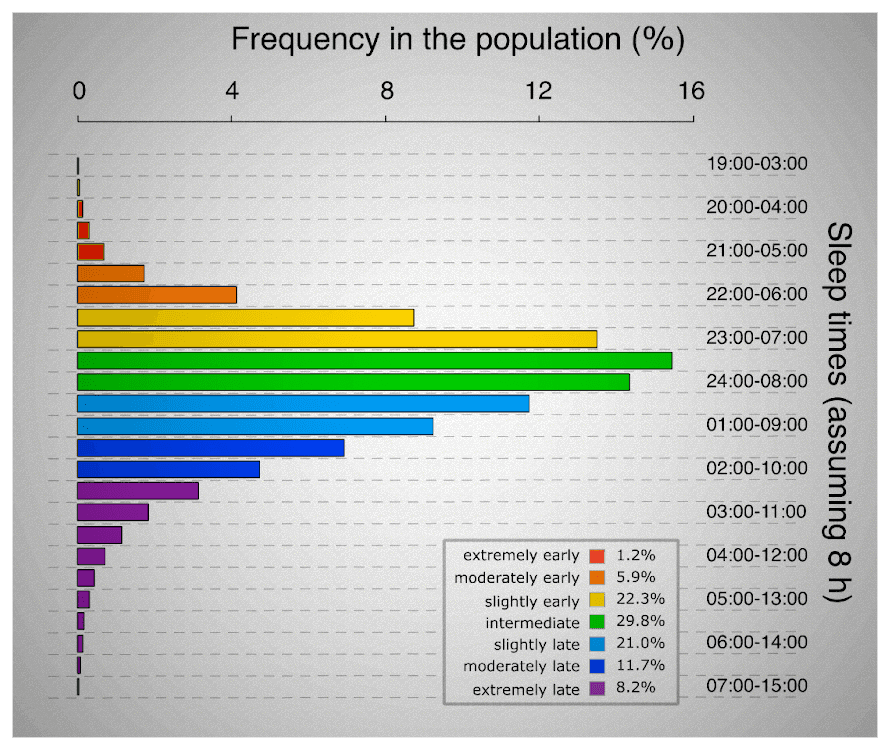

It is a common belief that going to bed and waking up early in the morning is the optimal sleeping pattern. This might not be true for many people, but research shows that this is actually determined based on one’s personal “chronotype”, which is determined by their unique internal biology.

The human body has its own biological clock, called the “circadian clock”. This so-called “clock” is composed of biological sensors that receive input from the environment about the time of the day, from the body about its state (e.g., when one last slept), and biochemical arms that regulate the body based on it [31-33]. On earth, this “clock” is naturally calibrated to be in sync with the 24-hour solar day, however, the circadian rhythm can be trained with strict scheduling to fit one’s life demands (e.g., their work shifts). On the other hand, one’s “chronotype” is their body’s genetically-determined [34] tendency to sleep in particular hours of the day, while performing tasks in others. For instance, one may be a “morning person” - tends to sleep early, performs tasks best in the mornings, and one may be an “evening person” - the other way around.

These are two extremes on a spectrum, most people fall in between. The chronotype has a strong genetic basis, and is deemed impossible to change [34]. Every individual’s genetic chronotype dictates sleep in specific hours of the 24-hour day that do not change. For instance, if one’s chronotype is to sleep at 22:00 tonight, it is very unlikely to shift the next day. With all that being said, it could be concluded that a “morning-type” athlete’s body could achieve better efficiency if they sleep early in the evening. On the other hand, an “evening-type” athlete’s body could achieve better efficiency if they sleep later in the evening. Hence, athletes could achieve a better performance, if they go to bed at the same hour every night/day, based on their own chronotype, or in other words, match their circadian rhythm with their intrinsic chronotype.

There is a scientifically-validated self-assessment questionnaire, called the Morningness-Eveningness questionnaire, which can determine whether one is more of a morning or an evening person [36]. You could use it to get an idea of your personal chronotype, and fine-tune your sleeping schedule.

Morningness-Eveningness

Questionnaire

This self-assessment consists of 19 questions and will help you determine your chronotype — whether you are more of a morning or evening person.

Based on the validated questionnaire by Horne & Östberg (1976)

To wrap up, it is recommended that every person sets up a sleep schedule that ensures the following:

- a 7-9 hour-long

- uninterrupted sleep

- in accordance with the personal chronotype

2. Choose a comfortable surface, and reserve it for sleep

After the sleep schedule is in place, it is important to make sure you fall asleep and stay asleep during the period dedicated to sleeping. First, ensure your sleeping surface is comfortable.

Second, it is recommended that the surface is only dedicated to sleeping. Research shows that avoiding other activities in the bed throughout the day could help with falling asleep when it’s time [37, 38]. For example, if one avoids miscellaneous activities (like watching Netflix, doing exercises or writing a dissertation) in their bed throughout the day, they will probably fall asleep more easily at bedtime. This helps rewire the brain, associating sensory inputs from the bed (e.g., its appearance, texture, and even smell) with sleep, which is very effective [37-39].

3. Have a simple sleeping “ritual”

Higher brain functions (such as attention, reasoning, problem solving, and consciousness) are “turned off” while sleeping. To help initiate sleep, it is helpful not to do tasks that elicit such functionalities before bedtime, especially if the task is associated with intrinsic rewards (i.e., positive emotions) [40, 41].

Gaming could be an example of such tasks [42]. “Rewarding” tasks activate the reward system of the brain. This system is designed to shape one’s behavior towards getting more rewarding stimuli. It is connected to various parts of the brain, and can activate the parts needed for performing the task [43]. When a task requires the brain’s higher cognitive resources, the reward system promotes wakefulness. As an example, when one is engaging with a complex, pleasurable task, through a series of behaviors, their reward system is activated, shaping a desire to continue those behaviors, and keeping the person awake for more reward [40].

Research shows that having a sleeping “ritual” before bedtime could help turn off the higher functionalities of the brain, and thus, initiate sleep more easily [44]. This ritual could be 30-60 minutes long, and should be calming [44]. Such a ritual could be initiated by having a small snack (further described below), and continued by any combination of meditating, listening to relaxing sounds/music, brushing teeth, changing into sleeping clothes, adjusting the room temperature, making the bed, and other similar activities [44].

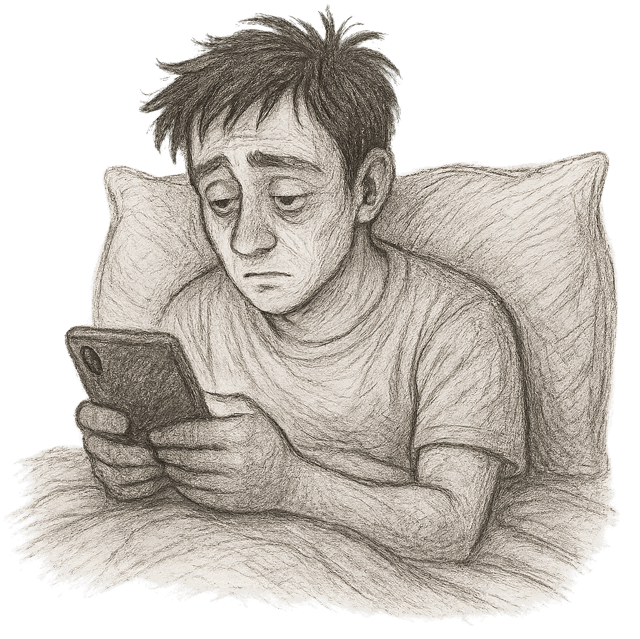

4. No devices with a screen when in bed

It is important not to use any device with a screen when in bed (especially not a smartphone). Modern algorithms (particularly in the social media, but also in the other media like the news and TV shows) are intentionally designed to be addictive, they do so through several neurobehavioral “brain hacking” techniques, most of which stimulate the brain’s reward circuits to encourage continued engagement with the media [45, 46]. As explained above, these circuits have strong inhibitory effects on sleep [47, 48].

Furthermore, research shows that looking at electronic screens (e.g., watching shows, reading online, texting, doom-scrolling, etc.), especially in the hours leading to bedtime, reduces the likelihood of falling asleep [49]. This is because the light from the screens (especially its blue component) initiates a series of signals when hitting the retina (the light-sensing layer in the back of the eyeball), ultimately causing a strong inhibition of the sleep hormone melatonin in the brain [50]. Hence, it is recommended to avoid screen time for at least an hour before bedtime.

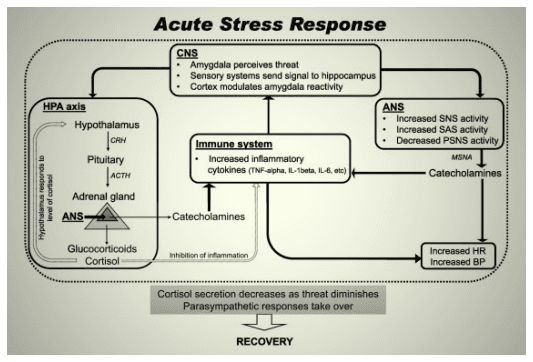

5. Exercise regularly, but at least 2 hours before bedtime

As mentioned above, exercise and sleep could optimize one another. But some studies show that exercising vigorously immediately before bedtime (i.e., 1-2 hours before bedtime) not only does not help the sleep, but makes it worse [51, 52]. This is because during intense exercise, the body goes through physical stress, which in turn initiates a “fight-or-flight” response through neurohormonal axes (which is also why the heart and respiratory rates increase, the muscles become tense, etc.). Two components of this “fight-or-flight” response are increasing of the core body temperature, and arousal of the brain, both in turn cause inhibition of sleep [51, 53].

The body’s responses to environmental stimuli take time to normalize. This includes the mentioned response to the physical stress during strenuous exercise. Thus, it is recommended that there is, at least, a 2-hour gap between strenuous exercise and bedtime [51-53].

6. Go to bed neither hungry nor full

A complex association exists between different degrees of hunger and wakefulness, which is under investigation as of today, but a general takeaway from many studies is that severe hunger arouses the brain [54, 55]. Moreover, research shows that consuming certain nutrients before sleep can help muscles synthesize proteins and accelerate metabolism, while having a minimal effect on the lipolysis (breakdown of fat) [56-59].

But having a full meal before bedtime could also disrupt sleep through indigestion and gastroesophageal reflux, digestion’s thermogenic effects(which increases the core body temperature, described below), glycemic spikes (sugar rush) and altered neurohormonal balance.

Therefore, it is usually recommended to consume [14, 60-62]:

- a full meal at least 4 hours before bedtime

- a small meal totaling less than 150 kcal, preferably rich in electrolytes, complex proteins, and high-glycemic index carbohydrates at least one hour before sleep

- but preferably, nothing within an hour of sleeping

7. Adjust the ambient temperature dynamically

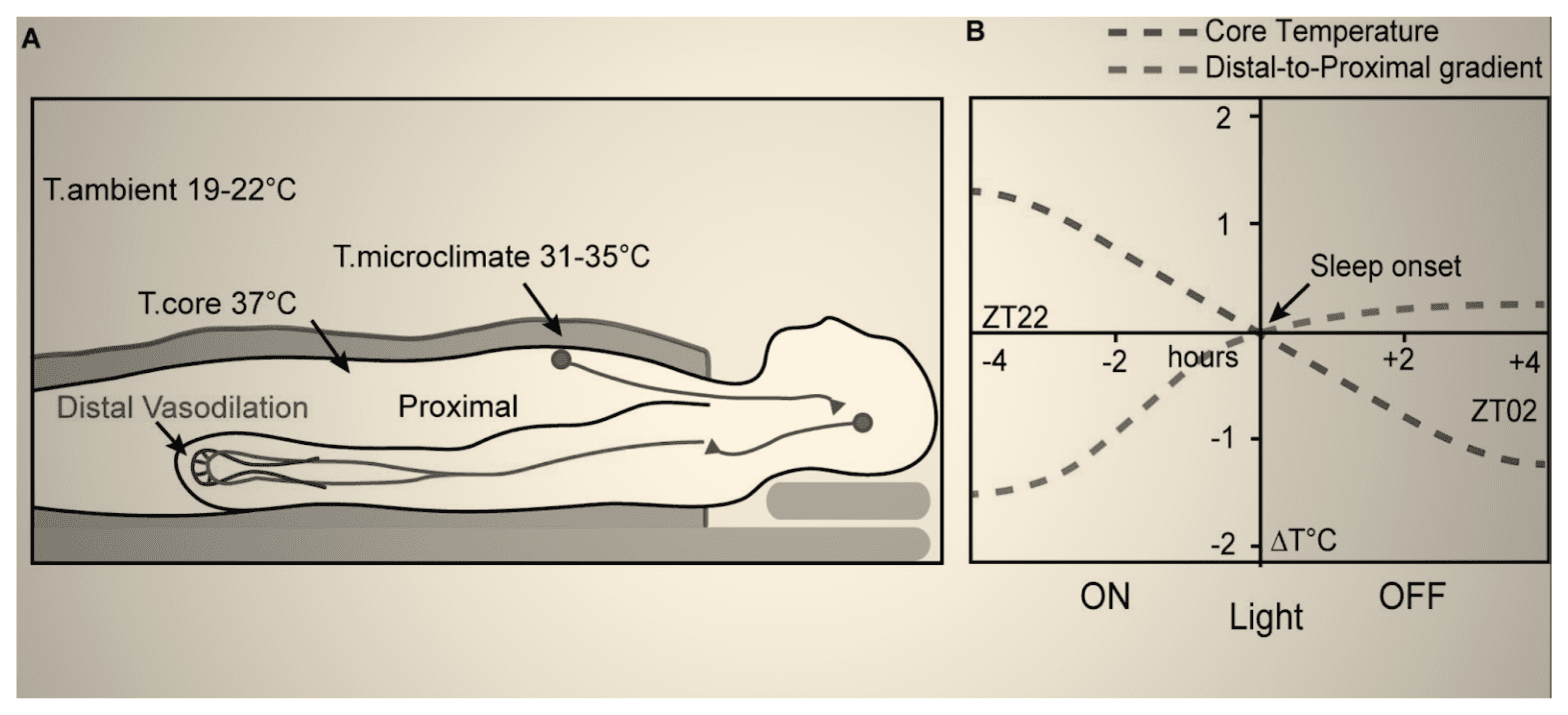

Sleep is basically a complex program that runs on the nervous system platform throughout the body. This program involves certain “checkpoints”, where the inputs of the afferent neural paths is checked, based on which, it proceeds to the subsequent stages. The body temperature constitutes one of these checkpoints [63].

Complex natural neural networks are able to sense the body temperature using special thermoreceptors [64]. During sleep, the body regulates the temperature of core organs (e.g., brain, internal organs) at lower levels, to help slow down their metabolism [63, 64]. The system does so by shifting the blood to the skin, thereby, taking and expelling the heat from the core organs.

Thus, the temperature of the exposed skin (e.g., over the hands and legs) increases when one is falling asleep [65]. This increase in the skin temperature is a cue for the program to proceed to its subsequent stages. We can facilitate sleep by helping the system pass these checkpoints. For example, studies demonstrate that warming up the arms and legs (thereby, promoting dilation of their blood vessels so that they can accommodate more warm blood and expel more heat) facilitates the reduction of the core body temperature, and in turn, falling asleep [66, 67].

Therefore, covering/warming them up can assist falling asleep. Meanwhile, it is important to help the core body temperature cool down (which is why it is not recommended to consume large meals before bedtime due to the thermogenic effects of digestion, as described above). This could be achieved by setting the ambient temperature to slightly lower degrees [68] . On the other hand, the body aims to reverse this process, “warming up” the organs before waking up. Facilitating this “warm up” by increasing the ambient temperature when waking up helps ease into it, thus, helping one feel more refreshed when getting up [63, 65, 68, 69].

Together, the current knowledge supports a dynamic control of the ambient temperature over the course of sleep, with the targets being slightly cooler temperatures before falling asleep, to slightly warmer when it is time to wake up.

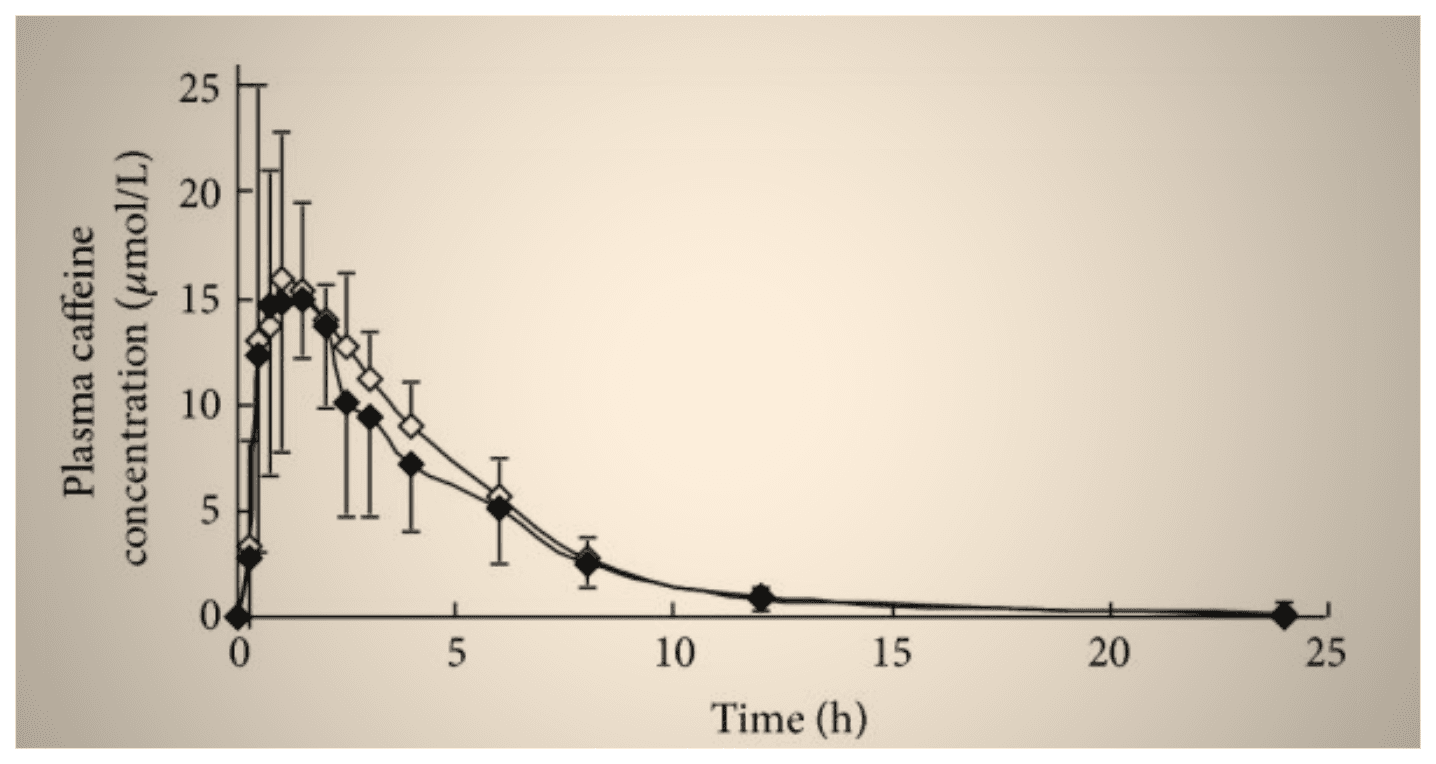

8. Limit stimulant intake from the afternoon onwards

Studies unanimously show that consuming certain substances like caffeine, nicotine, and ethanol significantly reduce sleep quality, by promoting arousal and disrupting the natural sleep circuits of the brain [70-72]. Thus, consuming products that contain these (e.g., coffee, (e)cigarettes or vapes, alcoholic beverages, among others), is discouraged from the afternoon onwards.

Specifically concerning caffeine, there is an active discussion among experts on whether to recommend taking it before exercise sessions (for example in the form of a pre-workout supplement), as it is shown to improve athletes’ physical performance but disrupts their sleep [73]. Although this strongly depends on individuals’ genetics,caffeine can be detectable in blood up to 12 hours after consumption, even a small amount of which is shown to negatively affect sleep [74].

In a recent study, moreover, caffeine improved participants’ athletic performance when taken before morning exercise sessions, but elicited no effect when taken before evening exercises [75].

Altogether, it can be concluded from the most recent evidence that, while controversial in evenings, taking caffeine before morning exercises is an optimal strategy to balance its positive physical effects with its negative effects on sleep. Nevertheless, as caffeine’s influence depends heavily on individuals’ genetic attributes, it is recommended to consult an expert in this regard to craft a plan based on individualized trials of exercise timing and caffeine intake [73].

9. Receive Exposure to Natural Light

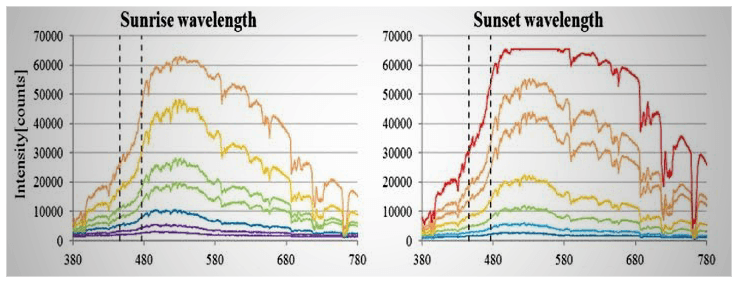

Natural light is a primary stimulus for the adjustment of the circadian clock [33]. In other words, regardless of one’s chronotype (described above), the brain constantly regulates the circadian rhythm by receiving sensory input from the retina (the light-sensing layer of the eye), and thus, adapts to the ambient lighting condition [33].

Two of the important features of the ambient light analyzed by the brain are [76, 77]:

- the variability in its intensity

- the variability in its spectral composition (its color)

Over the course of a day, the natural light first increases in intensity and shifts from longer to shorter wavelengths (becomes “bluer”). Then, its intensity decreases, and its composition shifts from shorter to longer wavelengths (becomes more “yellow/red”).

All of these subtle changes in the natural light, which are not seen with artificial light, are picked up by the retina, and are used to regulate sleep/wakefulness cycles [77]. Continuous exposure to the same ambient lighting conditions (constant intensity and color, as seen with artificial lights) desensitizes this key regulatory feature, thus, worsening the sleep quality [78].

Therefore, it is recommended to receive exposure to natural light throughout the day, or at least, use a dynamic lighting system to simulate natural lighting conditions in the living environment.

10. Managing comorbid conditions, CBT and pharmacological interventions

Many medical, psychiatric, and/or social problems exist, which can in turn, lead to serious sleep problems. These are called “comorbid” because they coexist with (and in many instances, give rise to) the main problem (poor sleep). These should be diagnosed and managed by experts of each respective field.

For instance, generalized anxiety disorder [79], benign prostate enlargement [80], and domestic violence [81] are all problems that can seriously harm one’s sleep. The first should be managed by a psychiatrist, the second by a urologist, and the third by social organizations (or even law enforcement). Consulting a professional is recommended to identify such comorbid conditions and get referred to the right expert.

Furthermore, if sleep problems persist despite good adherence to the mentioned recommendations and proper management of the comorbid conditions, sleep experts usually advise cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which is a well-studied, very effective type of psychotherapy.

Although various herbal remedies and medications exist to help with sleeping (ranging from Chamomile tea to antihistamines, melatonin, benzodiazepines, even antipsychotics), these are typically used only in adjunction to non-pharmacological interventions (such as CBT).

Due to their possible side effects and potentially addictive properties, such remedies or medications should be tailored carefully to one’s specific sleep problem by accredited sleep professionals. Thus, consulting one is recommended when sleep problems persist despite adhering to the sleep health recommendations.

What to do if you have already had a bad night of sleep?

As mentioned earlier, even a single night of bad sleep can initiate a spiral towards a progressive reduction in athletes’ performance. Yet, we are only humans, and poor sleep may sometimes be unavoidable. Like many other instances, it is important not to catastrophize the case of a single or few nights of poor sleep, but to maintain motivation and plan effectively to wash out its unwanted effects.

The first thing to do to this end, obviously, is to try to avoid more nights of bad sleep using the mentioned techniques. It would be better, additionally, to substitute highly technical coordination-based workouts with simple resistance/strength-based training after a night of suboptimal sleep.

This is because, according to studies, short-term sleep deprivation (e.g., lasting less than a week), while capable of initiating a decline in muscle strength, affects muscle strength less significantly than it does motor coordination and dexterity in the initial stages [3, 4, 6, 82, 83].

For calisthenics athletes, this means omitting specific skill work, aimed to increase coordination (like freestanding handstand work) and doubling down on more stable strength or hypertrophy focused exercises (like weighted dips or wall handstand push ups) could be a valuable strategy. While not necessary, we can take this strategy further and in some cases replace freeweight or weighted calisthenics exercises with more stable machine equivalents.

This rescheduling of exercises, would hence, help with managing expectations, while keeping one motivated to continue training. Withdrawing from exercise merely due to a night or two of bad sleep, in any case, can exacerbate the situation and cannot be considered a good idea.

Conclusion

In conclusion, sleep should be regarded as a cornerstone of an athlete’s daily routine, just like nutrition and exercise. Scientific evidence unanimously indicates that poor sleep quality can undermine healthy athletic practices in several domains, including physical and cognitive performance, recovery, and metabolism.

On the other hand, a healthy sleep can greatly improve one’s athletic performance. In simple terms, a healthy sleep acts like a “distress” signal that resonates in the body through the neurohormonal axes, thereby, increasing protein synthesis and fat breakdown, promoting muscle buildup and recovery, improving sharpness and coordination, while even modifying one’s unconscious behavior to become healthier.

An optimal state of sleep health can be achieved through implementation of simple evidence-based strategies, such as having and honoring a sleep schedule based on one’s chronotype, having a bedtime ritual, managing screen time, and creating a sleep-dedicated environment.

Our current knowledge generally indicates, moreover, that these strategies have a complementary and/or synergistic relationship. This means that none of them could be considered solely better and/or more necessary than the others, but they could complement and enhance each other’s benefits.

It could be difficult at first to overcome bad sleeping habits, but as indicated by science, only by doing so can athletes unlock their full potential in training and/or competition. Nevertheless, if a night or two of suboptimal sleep occurs, apart from using the mentioned techniques to break the cycle, athletes can reschedule their exercises by deferring their coordination-based exercises and focusing on more stable resistance training, until the adverse effects of those bad nights are washed out.

Disclaimer

The content of this article neither constitutes, nor is a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment of a licensed health care provider, all of which should be based on the licensed health care provider’s assessment of a person’s specific and unique circumstances. Furthermore, the content of this article is not meant to endorse/denounce the use of any service/product.